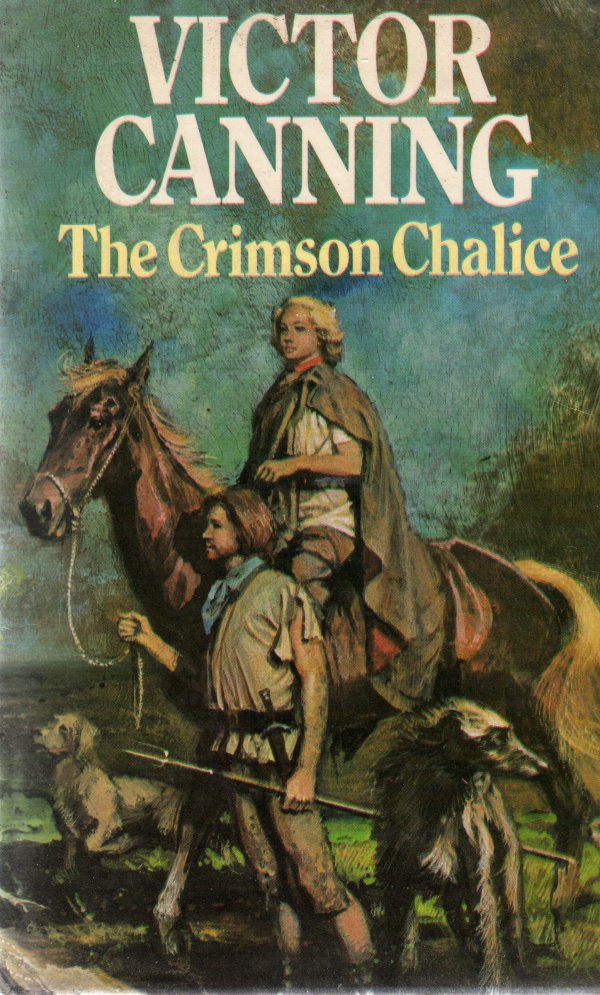

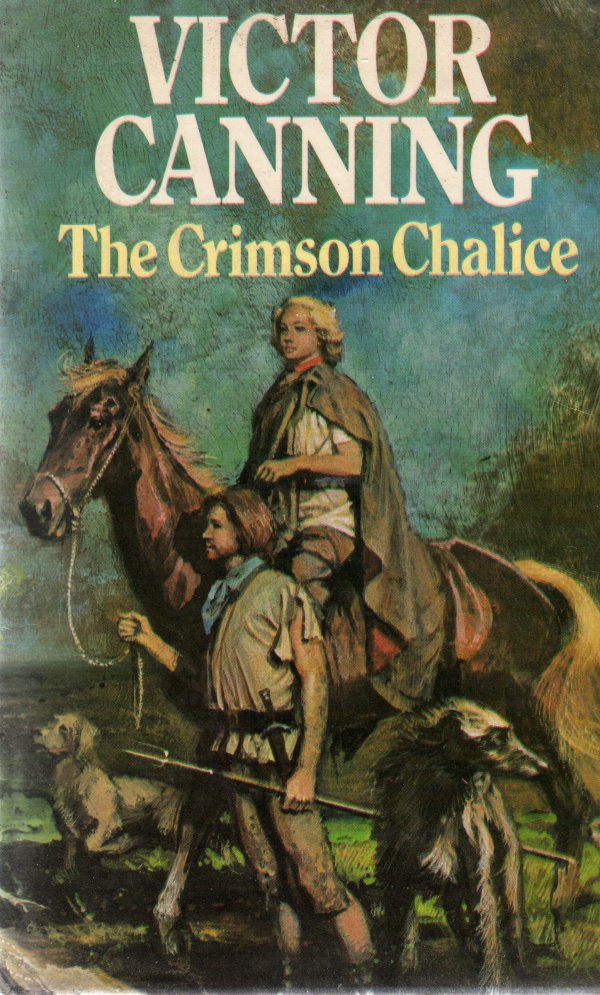

UK first edition

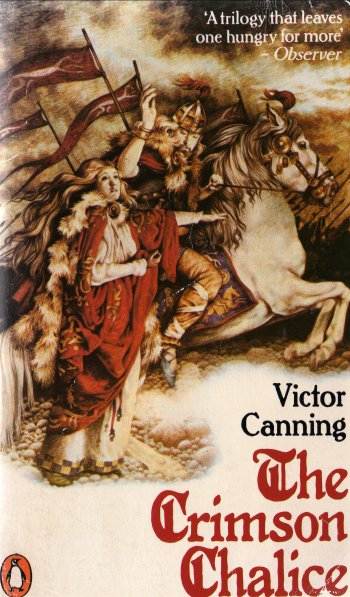

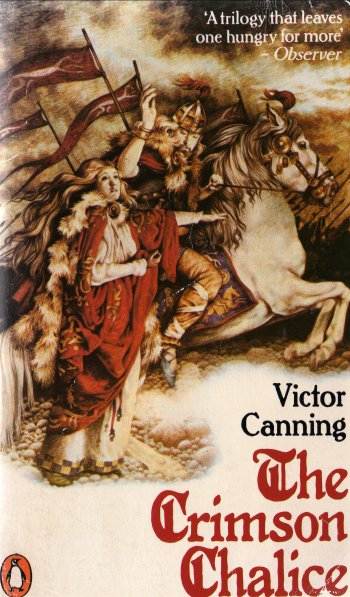

Penguin trilogy

UK first edition |

Penguin trilogy |

The BookIt starts with this note: ... and ends with this postscript:

In the main story Gratia, known as Tia, a Romano-British girl escaping from the looting and burning of her home in Anderida (Pevensey), comes across the body of Baradoc strung up on a tree and left to die by his treacherous cousin. She cuts him down and revives him. Baradoc with his three trained dogs and a raven, helps her to reach her uncle's house at Aquae Sulis (Bath). En route they steal a horse from a black corsair called Corvo, and defend a priest from three vagrants who attack his shrine. The priest gives them a chalice to look after, saying it had once held the vinegar given to Christ on the cross. Tia reaches her uncle's house, but it is soon raided by Welshmen, and she escapes being taken as a slave only because Baradoc can talk to the Welsh leader in his own language and declares they are betrothed. They make their way towards his own tribe in Cornwall, take a boat from a devious marsh ferryman who has tried to cheat them, and find themselves marooned on Lundy Island, where their boat is mysteriously stolen. Over the winter Baradoc tries to build a new boat and Tia finds she is pregnant. Baradoc meets the island's reclusive inhabitant, whose name is Merlin. While trying out the boat Baradoc drifts out to sea and is captured by the corsair Corvo. Meanwhile Merlin helps in the delivery of Tia's baby son. |

Publishing HistoryThis is the first part of a trilogy of novels re-telling the story of Arthur. It was published by Heinemann in 1976 at £3.10. There was a Companion Book Club edition in 1977. The second part, The Circle of the Gods, appeared in 1977 and the third, The Immortal Wound, in 1978. A paperback comprising all three books was published by Penguin in 1980. The first book includes a map showing places with Latin and modern names. The second and third books include a listing of personal, tribal and place names. Alan Lupack's encyclopedic Oxford Guide to Arthurian Literature and Legend (OUP: 2005) has this to say:

The book has the dedication "To my wife, Diana, with love". Diana was Canning's second wife. She died just before the book was published. Here more than anywhere else Canning indulges his enthusiasm for descriptions of countryside and animal and bird life. The style is readable and the story full of tension as well as colour.

|

Here are some pictures of the Roman Villa at Chedworth in Gloucestershire, which may have been in Canning's mind as he described the Villa Etruria of Tia's uncle (pages 107-110).

|

|

They had come to it by the road which ran west to the small port of Abonae near the mouth of the river, reaching it in the late afternoon, the lowering sun striping its red tiles with black ridge shadows while the breeze rippled the branches of a row of mixed limes and poplars that flanked the slopes on either side of the building. Part of the bank had been cut away and the villa had been built into it. |

In the centre of the courtyard was a spring-fed well, encircled with a carved stone parapet and roofed with an ornamental canopy from which hung a large bronze bucket. |

|

|

A little beyond it giving shade to the yard grew a tall sweet chestnut tree, a tree, Baradoc knew, which the Romans had brought to his country in their early days. When corn was short the old legionaries had milled the chestnut fruits to add to their scanty cornflour issue. |

For the first time in his life—for not even in his old master’s house had this happened to him—Baradoc ate in Roman fashion, reclining on one of the three sloping couches set around the low table and waited on by the steward. Although Truvius showed little hunger, shifting often, too, in discomfort from his rheumatism on his couch, he and Tia did full justice to the stuffed olives and preserved plovers’ eggs, the cold lobster—which had been brought upriver from Abonae—and the young broad beans and carrots, followed by slices of grilled venison, their appetite lasting right through to the dessert of dried figs and walnuts. Throughout the meal the steward had hovered round, refilling their wine glasses, bringing fresh napkins and water bowls for them to clean their hands, and watching always over the comfort of Truvius, ready to help him turn, prompt with a fresh cushion to ease his stiff body. |