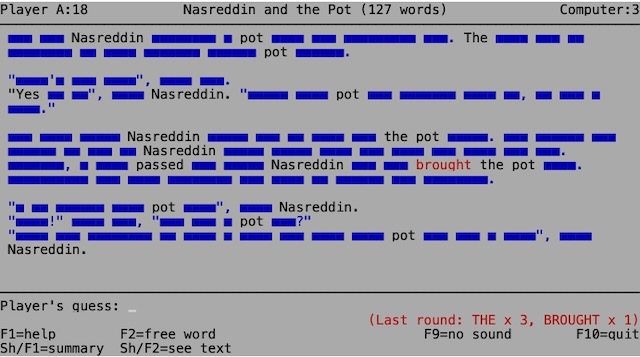

ECLIPSE is the latest embodiment of the total deletion computer program, one in which a student is faced with a screen on which all the words have been replaced by dashes or squares. The student's task is to guess words one at a time.

The program derives from a Tim Johns program known as TEXTBAG the earliest version of which goes back to 1980. TEXTBAG involved token replacement, one gap being pointed to and only one word supplied at a time; the alternative is type replacement, in which all occurrences of a guessed word are filled in. This second approach has had a dozen separate incarnations, of which STORYBOARD is the best known and ECLIPSE the most recent and most elaborate.

ECLIPSE differs from other versions in two main respects. The first is that one can play in challenge mode with the computer nominally competing against the learner and supplying words alternately; the advantage of this is that the learner is rarely completely stuck since the computer's words will suggest new lines of thought. The computer does not, of course, guess or make mistakes, but it is biased to select low-frequency words which score few points but tend to supply more information. The second main innovation with ECLIPSE is that one can tailor the starting appearance of a text by selectively displaying or deleting words of selected grammatical classes or words from specific vocabulary lists. The purpose of this is to make it easy to devise grammatically focussed or ESP-oriented forms of the activity.

This paper is in part a preliminary account of research work which will be submitted for a dissertation in June. Most of what we have to say would apply to any form of the STORYBOARD activity rather than specifically to ECLIPSE. However, the observations we have collected suggest that the availability of the challenge mode has done something to enliven the quantity and to some extent the quality of discourse.

What we have tried to do is collect data on various groups using the ECLIPSE program both for EFL and for Spanish as a foreign language. The subjects were all adults, consisting of classes of overseas students at Bristol University's English Language Support Unit and several classes of local authority evening class students, largely British, following Spanish courses at beginner and pre-intermediate levels. The data we collected consisted of a questionnaire filled in at the end of each working session and a full history of the session with every keystroke and every machine prompt recorded. The students worked in pairs or groups of three, which weakened any direct inferences connecting individual questionnaire data and task performance. However, it has been established informally but firmly that total deletion programs work best in a small group environment, and we did not want to collect data of the program in use in an untypical way. We did not record the speech of the group, though the teachers made informal observations about the group dynamics. About ten of the subjects were observed twice for a 90-minute session, the other twenty only once.

The overseas students were a polyglot group and therefore used English as their negotiating medium. The Spanish learners almost all had English as mother tongue or used it fluently. In general they used English as their negotiating language, with substantial reading from screen in Spanish and some barking of words or phrases. For their first session we used Spanish-only text, but we brought back one class for a second session using bi-lingual text. For this the programmer (Higgins) wrote a special version of the program which, in challenge mode, would generally prompt with words from the first half of the text. The researcher (Poyatos Matas) wrote a group of short texts and their translations, presented in half the cases Spanish first and in the other half English first. This was to try to discover to what extent learners would use word-level translation cues, or how far they would pursue hypotheses about sentence level meanings, disregarding the word cues randomly thrown at them by the computer in challenge mode.

The full results have still to be interpreted. The questionnaire responses report very high satisfaction with the activity, although we acknowledge that such data is highly suspect, since Hawthorn effects and novelty will skew the data. The questionnaires also show that learners in the bi-lingual session seemed in general not to be aware of their own strategies; asked to describe how much they used translation and in which direction, what most users reported was not borne out by the computer's record.

Very little evaluation of non-tutorial forms of CALL has been carried out with traditional academic instruments. Perhaps the main reason is simply the huge labour involved in setting up pre- and post-tests and administering them to populations of sufficient size. Nobody is currently funding that kind of research effort. What people have tended to do instead is to record sessions of computer work and transcribe the resulting discourse. Existing reports tend to re-establish what is easily predicted, namely that learners working in groups on a task will use the most open channel available to them, namely the first language in a monoglot class, and they use the smallest units of discourse that will get the job done. If the job, as in ECLIPSE, is to guess words, the discourse will largely consist of words barked at the group. A particularly trenchant article by Francis Jones in the latest issue of System (Jones 1991:2) describes a session with an adventure game and gives a sample of round-the-machine discourse which might discourage any novice from ever starting. In the article Jones reports that the richest interaction he secured arose from some of the simplest style of work, namely a reading maze, in effect a series of multiple choice questions.

Tony Howatt once said "Discussions on language teaching often imply that if the pupil is actively engaged in producing comprehensible foreign speech, then he is learning how to speak the foreign language. That is not a logical deduction at all." (Howatt 1969:12) He was discussing the use of drills, and one could interpret his remark as being in line with Krashen's view that language produced without a message being sent or received is not input for language acquisition. However, I do not think this is the total of what Howatt meant, and I think the converse is equally applicable, namely that a pupil may be learning to speak even when not producing comprehensible speech. Certainly floods of communicative speech events provide overt evidence of mental activity and the output can be recorded and monitored for quantity and accuracy. It is not possible to monitor internal mental processes.

Perhaps there is a danger in being too concerned with objectives and desired outcomes, of ends before means. The same Francis Jones article in System quotes with obvious approval Roland Nyns's remarks:

A teacher's starting-point in using CALL should not be the question “what can I do with my PC?” but rather “which medium is best suited to teach such-and-such a skill?” The answer to this latter question might be the blackboard, the video, printed matter, or the tape-recorder as the case may be. It is rarely the computer.

[Though we need to remember that the available computers of that era were usually incapable of playing sound or video. — JJH]

It seems very plausible that the learning objective should condition the choice of a medium, and the converse, the unthinking adoption of a medium for all purposes, is what one of the authors (John Higgins) was ridiculing in his Music-assisted-language-learning (MALL) article in System 1986. But there is a danger in being too ends-oriented, a danger in saying: if it is 9 o'clock on Tuesday, we have to learn to ask and answer questions about interrupted events in the past (or use the past continuous tense if your syllabus is still structural). After all, even if you intend to teach the past continuous, might you not still take into class a cartoon that has amused you from the morning paper, even though there is nothing to connect it with the grammar topic?

Language can almost be regarded as inherently unteachable. There is too much of it, too many words, too many rules, too many collocations, too many style choices. Teaching is a sequential and finite process. Acquisition is an unpredictable, non-linear, chaotic process in which prodigious achievements may be made or little progress perceived without the circumstances telling us why. Roger Bowers's recent paper on chaos at the TESOL convention included a reference to the mathematical article that launched the whole subject of fractal geometry: "How long is the coastline of Britain?" One could legitimately ask a similar question: "How big is the English language?" and spend a similarly infinite time not reaching the definitive answer.

Higgins, John. (1986) “Integrating [computers] with [foreign language] classwork: a fable.” System, 14, 2.

Howatt, A.P.R. (1969). Programmed learning and the language teacher. Longman

Jones, Francis (1991) "Mickey Mouse or state of the art?" System, 19, 1.